At It Again Political Cartoon Panic of 1893

The Gold Age in U.South. history spans from roughly the end of the Civil War through the very early 1900s. Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner popularized the term, using information technology equally the title of their novel The Gilded Historic period: A Tale of Today, which satirized an era when economic progress masked social bug and when the siren of financial speculation lured sensible people into financial foolishness. In financial history, the term refers to the era between the passage of the National Banking Acts in 1863-64 and the formation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. In this flow, the U.Southward. monetary and banking organisation expanded swiftly and seemed assault solid foundations but was repeatedly aggress past cyberbanking crises.

At the fourth dimension, similar today, New York City was the centre of the financial system. Betwixt 1863 and 1913, viii banking panics occurred in the money center of Manhattan. The panics in 1884, 1890, 1899, 1901, and 1908 were confined to New York and nearby cities and states. The panics in 1873, 1893, and 1907 spread throughout the nation. Regional panics also struck the midwestern states of Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin in 1896; the mid-Atlantic states of Pennsylvania and Maryland in 1903; and Chicago in 1905. This essay details the crises in 1873, 1884, 1890, and 1893; this set includes all of the crises that disrupted or threatened to disrupt the national banking and payments system. A companion essay discusses the Panic of 1907, the shock that finally spurred financial and political leaders to consider reforming the monetary system and eventually establish the Federal Reserve.

The Panic of 1873 arose from investments in railroads. Railroads had expanded rapidly in the nineteenth century, and investors in many early projects had earned loftier returns. As the Gilded Age progressed, investment in railroads continued, but new projects outpaced demand for new capacity, and returns on railroad investments declined. In May and September 1873, stock market crashes in Vienna, Austria, prompted European investors to divest their holdings of American securities, particularly railroad bonds. Their divestment depressed the market, lowered prices on stocks and bonds, and impeded financing for railroad firms. Without greenbacks to finance operations and refinance debts that came due, many railroad firms failed. Others defaulted on payments due to banks. This turmoil forced Jay Cooke and Co., a notable merchant bank, into bankruptcy on September 18. The banking company was heavily invested in railroads, especially Northern Pacific Railway.

Cooke'due south failure changed expectations. Creditors lost conviction in railroads and in the banks that financed them. Stock markets collapsed. On September xx, for the first time in its history, the New York Stock Exchange closed. Trading did not resume for ten days. The panic spread to financial institutions in Washington, DC, Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, and Georgia, too every bit to banks in the Midwest, including Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio. Nationwide, at least one-hundred banks failed.

Initially, the New York Clearing House mobilized member reserves to meet demands for greenbacks. On September 24, yet, information technology suspended cash payments in New York. New York'due south money center banks continued to supply cash to state banks. Those banks fulfilled withdrawal requests by drawing down reserves at banks in New York and in other reserve cities, which were municipalities whose banks could hold as deposits the legally required cash reserves of banks in other locations. The crisis subsided in mid-October.

The Panic of 1884, by dissimilarity, had a more than express affect. It began with a small number of financial firms in New York City. In May 1884, two firms—the Marine National Bank and the brokerage firm Grant and Ward—failed when their owners' speculative investments lost value. Soon after, the Second National Bank suffered a run later on it was revealed that the president had embezzled $3 million and fled to Canada. Then, the Metropolitan National Bank was forced to close after a run was sparked past rumors that its president was speculating on railroad securities with coin borrowed from the depository financial institution (those allegations after proved to exist untrue).

The latter institution had fiscal ties to numerous banks in neighboring states, and its closure raised doubts almost the banks to which information technology was linked. The crisis spread through Metropolitan's network to institutions in New Bailiwick of jersey and Pennsylvania, but the crisis was chop-chop contained. The New York Clearing Firm audited Metropolitan, determined it was solvent, advertised this fact, and loaned Metropolitan $3 1000000 so that it could withstand the run. These actions reassured the public, and the panic subsided.

The Panic of 1890 was also limited in scope. In November, afterward the failure of the brokerage business firm Decker, Howell and Co., securities' prices plunged. The firm'southward failure threatened its banking company, the Bank of North America. Depositors feared the banking concern would fail and began withdrawing substantial sums. Troubles began to spread to other institutions, including brokerage firms in Philadelphia and Richmond. Financier J.P. Morgan then convinced a consortium of 9 New York City banks to extend aid to the Bank of N America. This activity restored faith in the bank and the market place, and the crisis abated.

The Panic of 1893 was one of the most astringent fiscal crises in the history of the Us. The crisis started with banks in the interior of the country. Instability arose for two key reasons. First, gold reserves maintained by the U.S. Treasury brutal to virtually $100 meg from $190 million in 1890. At the fourth dimension, the United States was on the aureate standard, which meant that notes issued by the Treasury could be redeemed for a fixed amount of gilt. The falling aureate reserves raised concerns at dwelling and abroad that the United States might be forced to suspend the convertibility of notes, which may accept prompted depositors to withdraw bank notes and convert their wealth into aureate. The second source of this instability was that economic action slowed prior to the panic. The recession raised rates of defaults on loans, which weakened banks' residuum sheets. Fearing for the condom of their deposits, men and women began to withdraw funds from banks. Fear spread and withdrawals accelerated, leading to widespread runs on banks.

In June, bank runs swept through midwestern and western cities such equally Chicago and Los Angeles. More than than i-hundred banks suspended operations. From mid-July to mid-Baronial, the panic intensified, with 340 banks suspending operations. Every bit these banks came nether pressure, they withdrew funds that they kept on deposit in banks in New York Urban center. Those banks soon felt strained. To satisfy withdrawal requests, money centre banks began selling avails. During the fire sale, nugget prices plummeted, which threatened the solvency of the unabridged banking system. In early on August, New York banks sought to salve themselves past slowing the outflow of currency to the rest of the land. The outcome was that in the interior local banks were unable to meet currency demand, and many failed. Commerce and industry contracted. In many places, individuals, firms, and financial institutions began to use temporary expediencies, such every bit scrip or clearing-business firm certificates, to make payments when the banking organization failed to office effectively.

In the fall, the banking panic ended. Gold inflows from Europe lowered interest rates. Banks resumed operations. Greenbacks and credit resumed lubricating the wheels of commerce and industry. Notwithstanding, the economic system remained in recession until the post-obit summer. Co-ordinate to estimates by Andrew Jalil and Charles Hoffman, industrial production fell by fifteen.three percent between 1892 and 1894, and unemployment rose to betwixt 17 and 19 percent.one Afterwards a brief intermission, the economy slumped into recession again in late 1895 and did non fully recover until mid-1897.

While the narrative of each panic revolves around unique individuals and firms, the panics had common causes and like consequences. Panics tended to occur in the fall, when the cyberbanking system was under the greatest strain. Farmers needed currency to bring their crops to market, and the holiday season increased demands for currency and credit. Nether the National Banking System, the supply of currency could non answer quickly to an increment in need, so the price of currency rose instead. That price is known as the involvement charge per unit. Increasing interest rates lowered the value of banks' assets, making it more than difficult for them to repay depositors and pushing them toward insolvency. At these times, uncertainty about banks' health and fear that other depositors might withdraw first sometimes triggered panics, when large numbers of depositors simultaneously ran to their banks and withdrew their deposits. A wave of panics could forcefulness banks to sell even more assets, farther depressing asset prices, further weakening banks' balance sheets, and further increasing the public's unease most banks. This dynamic could, in turn, trigger more than runs in a chain reaction that threatened the entire financial organisation.

In 1884 and 1890, the New York Immigration House stopped the concatenation reaction by pooling the reserves of its member banks and providing credit to institutions beset by runs, effectively acting every bit "a central banking concern with reserve power greater than that of any European central bank,"2in the words of scholar Elmus Wicker.

A common result of all of these panics was that they severely disrupted manufacture and commerce, even after they ended. The Panic of 1873 was blamed for setting off the economic depression that lasted from 1873 to 1879. This period was chosen the Great Depression, until the even greater low of 1893 received that characterization, which it held until the even greater wrinkle in the 1930s—now known every bit the Keen Depression.

Another common result of these panics was soul searching about ways to reform the financial system. Rumination regarding reform was particularly prolific during the last two decades of the Gilded Age, which coincided with the Progressive Era of American politics. Following the Panic of 1893, for instance, the American Bankers Association, secretarial assistant of Treasury, and comptroller of currency all proposed reform legislation. Congress held hearings on these proposals simply took no action. Over the side by side xiv years, politicians, bureaucrats, bankers, and businessmen repeatedly proposed additional reforms (see Wicker, 2005, for a summary), but prior to the Panic of 1907, no substantial reforms occurred.

The adjective "gilded" ways covered with a thin aureate veneer on the outside but not golden on the inside. In some means, this definition fits the nineteenth century banking and monetary organization. The gold standard and other institutions of that system promised efficiency and stability. The American economy grew rapidly. The U.s.a. experienced among the globe's fastest growth rates of income per capita. But, the growth of the nation's wealth obscured to some extent social and financial problems, such equally periodic panics and depressions. At the time, academics, businessmen, policymakers, and politicians debated the benefits and costs of our banking system and how it contributed to national prosperity and instability. Those debates culminated in the Aldrich-Vreeland Deed of 1908, which established the National Budgetary Commission and tasked it to written report these issues and recommend reforms. The commission'due south recommendations led to the cosmos of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

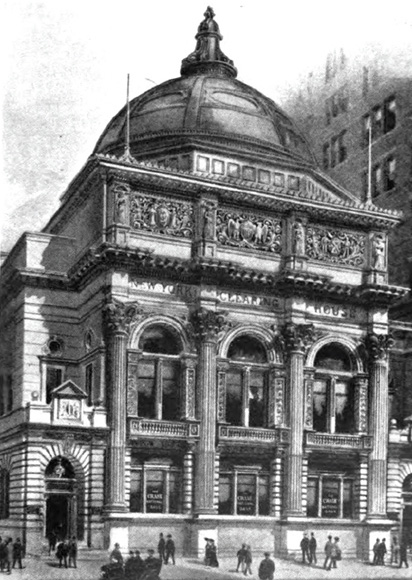

Drawing of the panic by Charles Broughton in: Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 18, 1893, p. 322 from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Sectionalization, reproduction number LC-DIG-ds-04499

espinozasunitoomas.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-panics-of-the-gilded-age

0 Response to "At It Again Political Cartoon Panic of 1893"

Postar um comentário